In general, good operating practice calls for regaining circulation before drilling ahead. However, in some companies, there is one notable exception: mud cap drilling. Mud-cap drilling permits continued drilling despite a pressured formation and a lost-circulation zone in the same interval of the open hole. Although mud-cap drilling has been employed in a limited manner in many oil and gas companies.

Mechanism

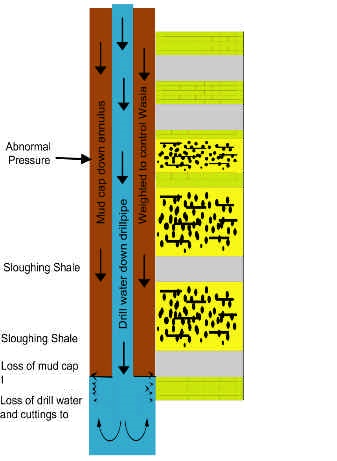

Drilling with a floating mud cap involves drilling ahead blind (i.e., without returns) by simultaneously pumping different fluid densities down the drill string and annulus. All fluid is lost to the thief zone. Figure B.4 illustrates this procedure, indicating the intervals exposed during the mud-cap drilling operation. Employing a mud cap in this manner allows continued drilling to the following casing setting depth, if circulation cannot be regained.

Note: Drilling with a mud cap through hydrocarbon-bearing reservoirs is not recommended, as the well kick may not be controlled from the surface (resulting in an underground blowout).

Application Of Mud Cap Drilling

This technique is utilized because some troublesome intervals must be penetrated and cased due to well-planning considerations. For example, the Wasia group (in Saudi Arabia – SA Oil History) consists of limestones, shales, and sands. Some of these shales can be highly water-sensitive. In addition, some permeable members of the Wasia can be abnormally pressured. Compounding these drilling complications is the Shu’aiba limestone, which underlies the Wasia group and is subnormally pressured and highly permeable. Given this situation, conventional drilling practice would suggest running and cementing casing at the top of the Shu’aiba but employing mud-cap drilling permits drilling to continue to the top of pay.

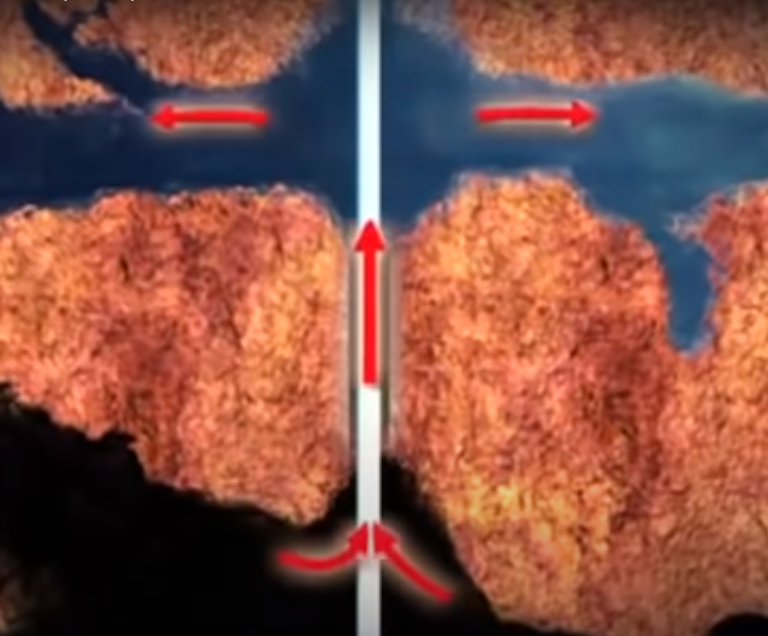

As noted above, the shale members of the Wasia can be highly water-sensitive. Contact with water or high fluid loss mud can cause them to swell rapidly and slough, resulting in a stuck pipe problem. Therefore, it is a drilling imperative that water not be permitted to contact the Wasia shales. An added complication is that some permeable sand members of the Wasia can be abnormally pressured, requiring mud densities ranging between 10 ppg and 13 ppg to contain them, with the norm around 12 ppg. Massive water flows evidence this abnormal pressure.

If unchecked, water flows from the Wasia would produce sloughing of water-sensitive shales situated above and below the Wasia sand members. Since the Shu’aiba is subnormally pressured, an inexpensive low-density fluid is required to drill it. In practice, fresh water (drill water) is used to drill through the Shu’aiba, and low-solids, non-dispersed mud is used to mud-cap the Wasia. The mud-cap mud is virtually untreated and is thus relatively inexpensive for its density. Ideally, in such a technique, water is the only fluid to contract the Shu’aiba, and mud-cap fluid is the only fluid to contact the Wasia.

Mud Cap Drilling Procedure

A general description of the typical mud-capping procedure follows:

- As drilling progresses, water is pumped down the drill pipe to remove cuttings from beneath the drilling bit and around the bottom hole assembly.

- These cuttings and the water are lost to the lost circulation zone. Meanwhile, the mud of a density sufficient to kill the pressured zone is pumped slowly into the annulus. Thus, a critical balance of pressure control is maintained.

- Field experience shows us that the premixed mud-cap mud barrels will be pumped down the annulus when circulation is lost to the troublesome zone.

- Drilling proceeds blind (i.e., no returns), pumping water down the drill string and adding mud down the annulus every hour.

- If partial or complete returns are regained while drilling, the mud pumps are shut down to determine whether the well is flowing or if partial circulation has been restored.

- Suppose it is determined that partial circulation is the case. In that case, the circulation loss zone is intentionally broken down by squeezing mud down the annulus to avoid drill water contacting any water-sensitive shales.

- On the other hand, if the well flows, the mud cap does not provide sufficient hydrostatic pressure. The remedy is either to increase the mud density or increase the frequency of the mud addition down the annulus. This assumes the reduction of hydrostatic pressure is due to more significant mud losses per hour than initially anticipated.

- Before any trip, the drill pipe is displaced with mud-cap mud.

- During a trip, 10 barrels of mud-cap mud are added every ten stands or every 30 minutes, whichever is less. While the pipe is out of the hole, 10 barrels of mud-cap mud are pumped down the hole every hour. Also, all these numbers can be modified according to field experience.

Conclusion

Mud Cap Drilling is a mix of art and science, requiring diligent monitoring. A stuck pipe could result if the pump rate down the drill string is too low. Also, if pump rates down either side are excessive, mud losses and mud expenses can become prohibitive. Conversely, if either injection rate is insufficient, the well could kick.

During mud-cap drilling, all kicks or suspected kicks are handled by increasing the injection rate of mud-cap mud down the annulus, squeezing if necessary. If the well is still not dead at the surface, the density of the mud-cap mud is increased until the well is killed at the surface. Naturally, any water flows (i.e., kicks) flow into the lost circulation zone. This practice has been used extensively over the years and has been demonstrated to be relatively safe.

References

- Aramco Well Control Manual

- Weatherford Video: Video 1

- “Pressurized Mud Cap Drilling Replacing Floating type to Reduce Risk and Optimize Costs.”, November 2020. doi